Jenny Buckham

Mark Scarth

Mentoring in sport – no more quick fixes

Jenny Buckham and Mark Scarth make the case for a more robust system for the development of mentors in sport and explain how the launch of the new qualification, the Level 3 Certificate in Mentoring in Sport, could mark the beginning of a new era for sports coaching

Jenny Buckham

Mark Scarth

The mentality surrounding British sport over the last two decades appears to be one founded on impatience and, more importantly, a lack of appreciation for the amount of time and commitment it takes to achieve excellence or expertise.

If we look to football, the sport that tends to dominate our country’s sporting landscape, we are presented with example after example of coaches and players cast aside because they did not achieve the success that was expected of them. Avram Grant was given one season to take a team of players he didn’t know and turn them into a top-class team that would be required to win trophies at the highest level, while playing the kind of football that can only be expected after years of careful planning and practice; of course he failed to live up to these expectations.

However, in comparison to Sam Allardyce, Grant was lucky in the amount of time he was given to achieve the almost impossible. Big Sam was only part-way through his first season when he was sacked because the fans and the board at Newcastle became impatient with the lack of success.

The Wimbledon Championships are another example of the impatience demonstrated by the British public when it comes to sporting success. The entire country based its hopes on Andy Murray, a 21-year-old who has undergone a significant amount of physical and technical training over the last year to try and equip his game for all surfaces. Although Murray reached the quarterfinals of a grand slam tournament and broke into the top ten rankings as a result, the majority of the British public did not consider him to have had a successful championship.

As a nation that historically dominated sport we appear to believe that we should be continuing to do so on a regular basis. However, the unfortunate truth is that we dominated many sports because we invented them and were better than the countries to which we then introduced them. We were successful by default rather than through the implementation of effective player development systems.

Where we are today is obviously significantly advanced from the days of colonialism and our governing bodies of sport have adopted a long-term approach to the development of their athletes. As Ericsson (1993) stated, it takes at least ten years of deliberate practice within a conducive environment to develop expertise and there is an acceptance of this fact when it comes to developing our athletes. Where this is not recognised as clearly is in the field of coach development.

With the appointment of national coaches from abroad for numerous sports (football, netball, swimming, etc) came the shocking realisation that as a nation we are not producing top-level coaches to support the development of our athletes. Although our coach education courses now include the ‘how to coach’ skills as well as the technical knowledge of a particular sport, there is still not enough thought given to supporting the coach within the practical environment over a long period of time. Research has demonstrated that knowledge can be increased through attendance at coach education courses but this does not automatically improve the overall effectiveness of the coach (Abraham and Collins, 1998). Attendance at formal or non-formal courses merely results in the learner achieving a training performance standard (TPS) that is sufficient for them to pass the course. It is essential that the learners then be supported in the application of the knowledge they have acquired if we are to move them to an operational performance standard (OPS) as quickly as possible. We must also accept that these courses are steps along the journey towards expert status and are not the journey itself.

If we are to develop expert coaches we must support the ten years of deliberate practice it will take and one way to do this is by mentoring. Ask ten people what mentoring is and you will get ten differing responses. Mentoring in nursing and education tends to be provided to help trainees become qualified (TPS), whereas in business it tends to be about improving a person’s performance ultimately to hit the bottom line. Mentoring in sport traditionally tends to be of a technical nature and seldom is mentoring utilised to develop the whole person through a life-long approach to learning.

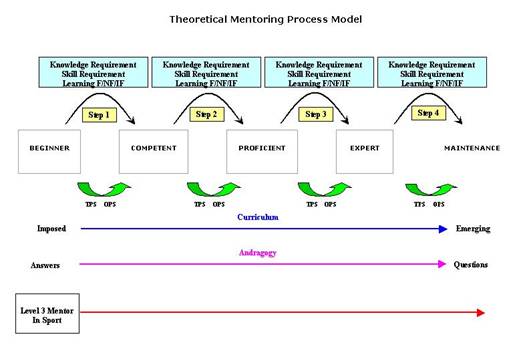

Currently approximately 25% of our coaches reach proficient status with few achieving expert levels [see reference below]. Currently experts also tend to be perceived as those working at elite levels of sport and we must work hard to educate people in the need to have experts working at all levels of the player pathway. Why can’t I become the best coach of under-sevens in the world? Sport has the opportunity to take a different view of mentoring and utilise it to increase the quantity of coaches reaching the higher levels of expertise. Sportcoach UK is working to develop mentors who are facilitators of life-long learning and not merely technical experts in their sports. Over the last two years Sportcoach UK has worked in partnership with Sussex Downs College and 1st4sport qualifications to develop a Level 3 Certificate in Mentoring in Sport. The qualification has the aim of giving mentors skills that will help them move learners from beginner to expert as illustrated in Figure 1.

One reason why people’s perceptions of mentoring vary so much is that the needs and wants of learners are dependent on their stage of development and thus mentoring programs have been designed to work with a variety of groups. Mentors in sport, if working on a life-long learning basis, must be able to facilitate what learners need when they need it and must therefore adjust the learning opportunities provided as the learner develops. This is highlighted in Figure 1 where at the beginner level the curriculum is imposed because learners need very specific knowledge and skills; at the expert level the curriculum is emerging and very much determined by the learner. This shift in curriculum is also coupled with a shift in andragogy (teaching of adults) as the need to increase levels of self-reflection and insight rise if we are to develop levels of expertise.

Figure 1: the Theoretical Mentoring Process Model

As previously stated, sport traditionally sees a mentor as a person with a higher level of technical skills, meaning that to mentor a level 2 Kabbi coach one must be a level 3 Kabbi coach. This tends to result in the focus of the mentoring relationship being sport-specific and technical/tactical in nature at the expense of all other attributes that we need to develop in a coach if they are to develop their expertise. This approach also tends to lead to reluctance to question current or traditional practice and can stifle original thought and innovation. A major problem with this approach is seen again in sport in the area of workforce development where the same people are fulfilling multiple roles: to be a level 1 tutor one must be a level 2 coach, to be an assessor one must be a level 2 coach, etc. Utilising mentors to be facilitators of learning opens up mentoring to a new pool of talent. Why can’t we give our fourth team skipper or club treasurer the skills and knowledge to mentor if they have the right soft skills to build relationships and intelligence to apply that knowledge? Why can’t we train and employ/deploy a pool of mentors to work in any area of sport and across sports? The Level 3 Certificate in Mentoring in Sport is designed to assist mentors in recognising a learner’s stage of development and then to act appropriately, adjusting the curriculum and andragogy to suit. Other sports development specialists, who can then provide the learning opportunities identified by the mentor and learner at the correct time, provide support for the mentors. This relationship is highlighted in Figure 2.

Figure 2: the mentoring relationship

As can be seen from Figure 2, it is the responsibility of the mentor to facilitate the correct learning opportunities at the correct time. The mentor can, with the help of others, provide access to technical and tactical advisors of a sports-specific nature, specialists such as nutritionists or biomechanics, co-coaches who exhibit good level of the vital ‘how to’ coach skills and a vast range of others. Knowledge of these areas can be provided in a manner to suit the learner if the mentor has been trained to do so. At times the mentor may have this knowledge and skills themselves but it should not be a prerequisite. If mentoring is about life-long learning and developing our levels of expertise why can we not use mentors or coaches from business to help our coaches attain these higher levels and grab the opportunity to expand our workforce?

Finally, how many of us over the course of our years of coaching have had little or no support? How many have attended coaching courses to be left alone to sink or swim post course? If we learn by our own experiences we will spend a lifetime doing it. Can we take this opportunity to stop thinking ‘sports-specific’ and start thinking of all the areas of knowledge and skills required to develop expertise? Can we start to think about life-long learning and accept that qualifications are a step along the road and not the journey itself? Can we open up our pool of coach developers to others with suitable skills and enhance our ability to offer learners support and guidance?

Jenny Buckham is coaching systems manager (London and the South East) and Mark Scarth is regional manager (South East) with Sportscoach UK. Both have worked and volunteered in sport for many years. The opinions expressed in this article are their own do not necessarily reflect the views of Sportscoach UK

For more information on sports coach UKs work in this area, and the ‘Level 3 Certificate in Mentoring in Sport’ please contact mscarth@sportscoachuk.org or go to www.sportscoachuk.org

Reference:

Chapter 11 - The development of expert coaching, by Paul G. Schempp, Bryan McCullick and Ilse Sannen Mason in The Sports Coach as Educator, Volume 1 Part 3. June 2006, ISBN 978-0-415-36760-8

The Leisure Review, August 2008

© Copyright of all material on this site is retained by The Leisure Review or the individual contributors where stated. Contact The Leisure Review for details.