The Hoerengracht: a tableau of Amsterdam street life

The Hoerengracht: art in action

The Hoerengracht is a remarkable work of contemporary art that also serves as social commentary, a statement of political intent, a historical record and a challenge to the modus operandi of the National Gallery. Jonathan Ives considers the implications of a Dutch street scene in a London institution.

The Hoerengracht: a tableau of Amsterdam street life

The Hoerengracht is a street scene in three dimensions created by Ed Kienholz and Nancy Reddin Kienholz. First exhibited in 1984, the Hoerengracht is an imaginary area of Amsterdam, the name of which plays upon the names of rather more salubrious streets, such as Prinsengracht and Herengracht, and depicts a street in Amsterdam’s red light district. In its detailed portrayal of Amsterdam’s prostitutes and their working premises it is a representation of a famous aspect of the life of the city, real enough to make the viewer uncomfortable but also a work of art that has come to serve as an historical record of a city that has changed its attitude to much that made it famous around the world.

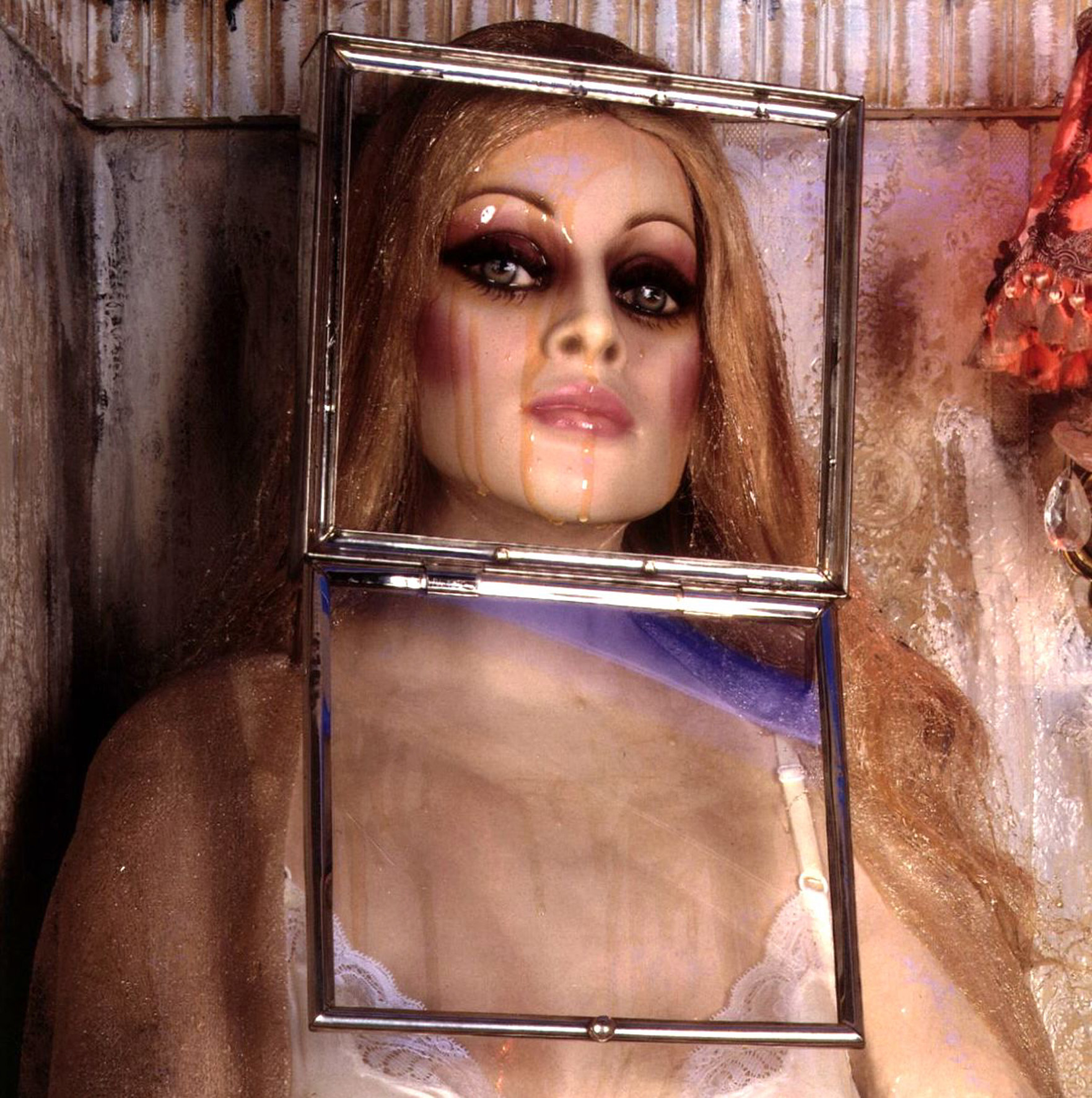

There are six rooms on the Hoerengracht, all of them unsettling in their detail and their implications. The streets in which the rooms are set present an urban scene: steel bollards and bicycles in racks; leaves in the kerb and a lone bicycle wheel still locked to a stand; a local radio station (here a London station) can be heard. In the rooms themselves the minutiae of domesticity, the detailed mundanity of a domestic industry, is one of the most compelling aspects of the installation. Through the windows one can see the cassette recorders and the china dogs that one might have found in any house in the city at the time, net curtains and flock wall paper that might almost be homely. A girl sitting in a rocking chair, her feet on a low stool while she flicks through a magazine, could provide an intimate image of someone at home if it were not for the fact that she is dressed only in her lingerie – her work clothes – and a square frame with a closable door surrounds her face.

As a work of art it is disturbing in its accuracy, evoking feelings of voyeurism and prurience in the viewer, but it also represents an oddity in the National Gallery. “The National” does not usually offer a home to contemporary art or sculpture but the Hoerengracht is both. As such it is jarring not only in its subject matter but in its modernity and its form. It is an issue that did not escape the attention of the National Gallery director, Nicholas Penny, when he opened the exhibition of the Hoerengracht last November accompanied by Nancy Reddin Kienholz, whose husband and collaborator, Ed Kienholz, died in 1994. “I was persuaded that this was a good idea,” Penny said. “This is an extremely serious exhibition and it does not in any way glamorise or romanticise prostitution. The connections with the more traditional art in the National Gallery are genuine.”

Colin Wiggins, the National Gallery’s head of education and the curator of this exhibition, explained that the inspiration for bringing the Hoerengracht to the National Gallery had come from a Kienholz exhibition at the Baltic in Gateshead some four years before. Having waited for a similar show to come to London, he realised that he would have to do it himself and the resonance of this distinctive piece of modern Amsterdam with the National Gallery’s collection struck him from the outset.

“My first reaction was that walking into this work was like walking into the streets in the works we have in the National Gallery,” he explained. By way of demonstration, a number of the gallery’s own seventeenth century Dutch works were hung in adjacent rooms. Jan Steen’s A Woman at her Toilet and Interior of an Inn, Godfried Schalcken’s A Man Offering Gold and Coins to a Girl and Pieter de Hooch’s A Musical Party in a Courtyard all serve to illustrate that the buying and selling of sex has been happening on the walls of the National Gallery for many years.

“The National Gallery is not a contemporary art gallery but we do have a rolling collection of contemporary displays with a view to shedding light on our collection,” Wiggins said. “And we have many pictures that show scenes far more repellent than the Hoerengracht but because we put them in gold frames they are safe.”

Delighted as he was to be able to show the Hoerengracht, Wiggins confessed that he had been even more excited to have been able to work with Nancy Reddin Kienholz in preparing the installation for display in London and he was pleased to be able to introduce her at the exhibition’s opening to explain how the work was created.

“We began building the Hoerengracht which was inspired by the red light district in Amsterdam,” Kienholz said. “Ed said he wanted to build this piece because the light in the windows is so beautiful. I never believed this. We began in Amsterdam doing research and taking photographs. There our friend Ad Petesen introduced us to the artist Onno Hooymeijer, who acted as our guide and translator. We took countless trips to Amsterdam for materials and photographs. It is not easy being a woman photographing prostitutes but after a while they came to trust me. Once the word got out that there were two crazy Americans willing to give 50 guilders for a four-minute photograph of the interior of a working girl’s room we were greeted with smiles and waves.”

Only the frames around the faces stand out from the realism of the depiction of the city’s working rooms in the 1980s. It was, Kienholz explained, a physical representation of a psychological phenomenon: “They have boxes around themselves so that they can shut themselves off.” She professed herself thrilled to see the Hoerengracht at the National Gallery. “It looks beautiful,” she said. “For living artists there is no greater place in the world than the National Gallery. For me personally this is as good as it gets.”

As the March 2010 issue of The Leisure Review went to press the Hoerengracht was being moved from the National Gallery to the Amsterdam Historical Museum and it is interesting to speculate on the impact of location on perceptions of the Hoerengracht as a work of art. In London it sat within the tradition of the European masters and their depiction of urban life and lives; in Amsterdam it becomes an historical record in a city that has only recently changed its attitude to prostitution. A sign on the wall of the National Gallery was explicit in Kienholz’s political aspirations for the Hoerengracht: “I would like the viewer to remember while walking the streets, ‘Let he who is without sin cast the first stone’… I would only hope that the Hoerengracht is a kind portrait of the profession and that eventually prostitution will be legal.”

At the London opening Kienholz had explained that prostitution had only become illegal in Holland in 2000. The long tradition of tolerance had been overturned, ostensibly in an effort to tackle the trafficking of women for use in the sex industry, but the result had been the government exerting a much greater level of control on how and where prostitutes worked. Where once there was flock wallpaper and an ersatz domesticity, the working rooms of modern Amsterdam are now white-tiled and functional, hygienic and perfunctory. In Amsterdam the Hoerengracht will sit within a very different context to that of London. If nothing else, Kienholz observed, the Hoerengracht does serve to open debate on the political and social issues of prostitution wherever it goes on show.

The Amsterdam Historical Museum is online at http://www.ahm.nl/

The National Gallery is online at http://www.nationalgallery.org.uk/

The Leisure Review, March 2010

© Copyright of all material on this site is retained by The Leisure Review or the individual contributors where stated. Contact The Leisure Review for details.

Download a pdf version of this article for printing

In the frame: a detail of the Hoerengracht

Nancy Reddin Kienholz and Colin Wiggins

Top and middle images: Edward and Nancy Reddin Kienholz © Kienholz Estate, courtesy of L.A. Louver, Venice CA

Above: courtesy of TLR Communications Ltd