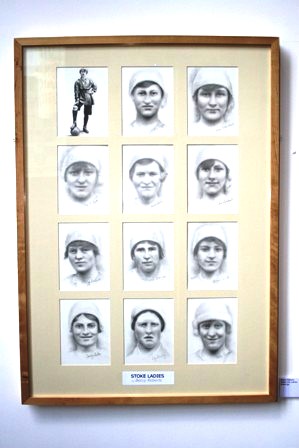

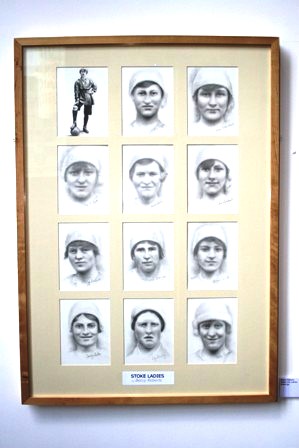

On the ball: Stoke Ladies

Right on museum of the Left

Drawn to the People’s History Museum by an exhibition around women’s football, Mick Owen was taken aback by Manchester’s only designated national museum.

On the ball: Stoke Ladies

The redevelopment of Manchester’s city centre has been going on apace for decades now with over-designed commercial developments cheek by jowl with chunky accommodation blocks offering the would-be city dweller “loft living”, or “flats no bigger than a shoe box” as somebody’s nan was bound to have said. The city has suddenly developed “quarters”, like Paris if you will, and even a Left Bank, although, delightful as the allusion may seem, the Irwell is a muddy ditch compared to the Seine and the view over Salford Central Railway Station is some distance aesthetically from Montmartre.

Squatting on this newly designated Left Bank, or Gartside Street as it used to be called, under the eaves of a citrus and steel creation housing the Manchester Civil Justice Centre is a reminder that this part of the world, and this part of town, has a gritty and grimy past that belies the modern gentrification, showing it up for what it is, pretension and hollow pomp. The fact that The Leisure Review’s site visit took place on the eve of the Windsor wedding may well have edged the day with a certain proletarian cynicism but for all its “extraordinary Cor-Ten metal shell”, its “exciting new programme of cross-curricular learning opportunities for early years, primary schools and secondary schools” and its café bar offering “hand-crafted coffees, seasonal British cuisine or fine local ales” the soul of the museum is in its original building – it used to be a pump house providing power throughout the city – and its exhibitions which speak of the history of working people in Britain.

The exhibition that drew us to the corner plot, just a thespian’s projected cry from the Granada Studios which spawned the first working class soap opera, Coronation Street, and a screeching guitar solo from where the Hacienda used to be, is called Moving the Goalposts, an examination in art of the history of women’s football. All this fits.

Women started playing football at about the same time as they started driving ambulances and working in munitions factories during the First World War. Dick Kerr’s Ladies, a works team from Preston, played in front of over 50,000 people and the Football Association, with the vision that it still brings to its work, banned women’s football from football league grounds in 1921. Fifty years later this ban was lifted and the game has grown to the extent that this spring the Women’s Super League, an eight-team, semi-professional division that will be contested through the summer while men’s teams are dormant in an attempt to garner greater coverage, opened for business. It is a sad indictment of both of Manchester’s football businesses that the conurbation is not represented in this, or any other, top-flight women’s league.

Both eras are represented in the exhibition which carries the work of twelve artists’ largely naturalistic representations of football and footballers. The images most often used to promote the portable exhibition are Beccy Roberts’ Lily and Dolly and England v Finland. Hung next to each other and linked stylistically and by subject (each image portrays two players in close contention for the ball), the pictures are accessible, colourful and not particularly challenging. Much like the rest of the exhibition. The only whiff of contention comes with the inclusion of a triptych portraying Richard Keys, Andy Gray and the female referee who was the catalyst of their demise, Sian Massey. Women’s football has been marginalised and patronised. Its growth has been as much about gender as about sport. The politics of sexuality have at times been a driver. None of this is addressed in what is a disappointingly small and anodyne examination of a singular and surprising narrative.

The location of Moving the Goalposts, a room shared with the product of an International Woman’s Day project ostensibly about making a quilt but involving festooning the Engine Hall (which is what the space used to be) with washing lines of labelled bras, serves to point up the fomer’s lack of scale and paucity of ambition. That the latest comment in the visitors’ book is “El futbol es para les hombres” indicates that there is a war to be won and gentle retrospectives, while attractive and quirky, will not push back any barriers, or storm any barricades.

The Engine Room functions as a community resource offering space and time to local groups with a story to tell or a point to make which, wherever possible, are “relevant to the story told in the museum”. In July, August and September the room will see a collection of “images and objects collected from people who lived in Salford’s now demolished terraced streets”. Called Retracing Salford, the exhibition will capture memories from a time before the slum clearances of the sixties and seventies and will include a surprisingly large number of old street signs. Whether any of the street names are as unlikely as that on a sign spotted not 100 yards from the museum’s front door is doubtful. Dolefield runs parallel to Gartside Street and, sadly, is not the former site of Manchester’s DHSS building. It seems that Robert Owen, “Britain’s first Socialist” and an advocate of co-operative living, made spinning mules in Dolefield in the early 1790s, when Manchester was one the crucibles of the Industrial Revolution.

Not many cities could carry off a People’s History Museum housing Spanish Civil War posters, Thomas Paine’s death mask and Keir Hardie’s pit lamp but Manchester does so with insouciance. The interior is light, airy and welcoming and the interpretation graphic and accessible. The café attached really is very pleasant and their claim to have “the sunniest riverside terrace” in Manchester is an example of the nicely judged irony for which the city is known. It is grim up north and for the working class it always has been but that doesn’t mean you can’t smile now and again, does it?

Mick Owen is the managing editor of The Leisure Review and a northerner by inclination if not birth.

The Leisure Review, May 2011

© Copyright of all material on this site is retained by The Leisure Review or the individual contributors where stated. Contact The Leisure Review for details.

Download a pdf version of this article for printing