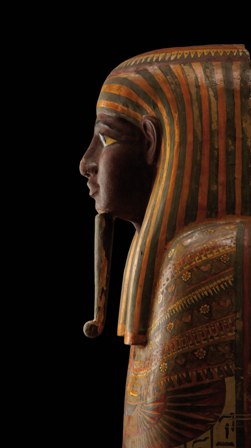

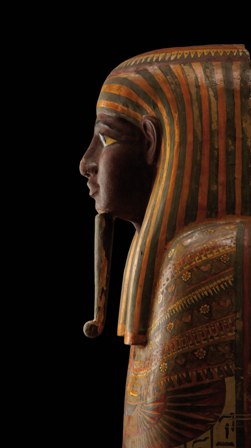

One of the stars of the Ashmolean's collection

image courtesy of the Ashmolean Museum

Ashmolean redux: the Egyptian collection

Two years after The Leisure Review reported on completion of the first phase of the Ashmolean’s redevelopment programme, Jonathan Ives dropped in to have a look at phase two, a £5-million project to open six new galleries for the museum’s collections of Ancient Egypt and Nubia.

One of the stars of the Ashmolean's collection

image courtesy of the Ashmolean Museum

The Ashmolean’s six new galleries represent the second phase of its redevelopment programme, a programme that has dramatically transformed one of the UK’s most august museums. In comparison with the scale, cost and impact of the first phase, in which £60 million was spent to double the museum’s gallery space and reinvent the building from a visitor’s perspective, these new galleries could be seen as something of an afterthought. However, the Ashmolean’s Ancient Egyptian and Nubian collections are among the finest in the country, with the Predynastic and Protodynastic material widely regarded as some of the most significant artefacts in the world. The new galleries provide these collections with a spacious new home and the museum’s Ancient World displays with a new coherence, thus completing the Ancient World floor that comprises artefacts from the world’s great ancient civilisations. The Ashmolean is confident that its £5 million has been well spent.

The space occupied by the new development includes a restoration of what had once been called the Ruskin Gallery. Previously commandeered by the museum shop as part of an earlier refurbishment, the reclaimed Ruskin Gallery now serves as the entry point for the new galleries of Ancient Egypt and Nubia. The Ashmolean’s Egyptian collection includes some 4,000 artefacts that represent 300 years of collecting, along with the Shrine of Taharqa, the only free-standing pharaonic building in Britain, and the twin statues of the fertility god Min, which are among the oldest preserved stone sculptures in the world.

These statues of Min dominate one’s first impressions of the new space, towering over the entrance to the gallery and setting the dramatic tone of the collection’s display. Despite dating from around 3,300 BC, the limestone gleams under the lights and the statues have a surprisingly contemporary aesthetic. Although the statues’ phalluses have not survived the millennia, the connection to fertility rites is clear enough. They are largest artefacts excavated in 1893-94 by Sir William Flinders Petrie at Koptos and this gallery includes many other items that combine to make the Ashmolean’s early Egyptian collection among the most significant outside Cairo. Near the statues the first of several clear timelines of Ancient Egypt offer a helpful historical perspective, allowing the visitor to place the artefacts in context and fill in any gaps in a less than perfect knowledge of Egyptian history

Moving through the galleries the visitor is able to trace the development Egypt as a region, a civilisation and a nation but there is, by virtue of the nature of archaeology, an emphasis on the development of burial practices and traditions along the Nile valley. As the power of Egypt’s rulers increased so did their tombs. Around 3,050 BC the first kings of a united Egypt emerged and their deaths were marked by tombs with back structures and underground chambers filled with the goods required in the afterlife. Pharaoh Djoser’s step pyramid tomb was the first large-scale stone structure in Egypt and by the 4th Dynasty the age of the pyramids had begun.

The second gallery is dominated by the Shrine of Taharqa, which was originally constructed around 680 BC as part of a temple complex in Nubia during the 25th Dynasty. Its scale and the detail of its carving reward inspection and serve to delay the visitor even though they are by now in sight of the gallery bearing the title Life after Death in Ancient Egypt with its displays of mummies and coffins, bodies and sarcophagi. Such intimate visions of life and death remain compelling even though they have become a conceptual shorthand for all things Egyptian. The nine-step process of mummification is explained on several monitors around the main display cases, revealing in just enough detail how the body was prepared for its funerary rights. In the central case a skilfully displayed body hangs above its coffin and below its coffin lid, like a three-dimensional recreation of an exploded illustration from the Haynes manual on Ancient Egypt.

Continuing through the galleries continues the story of Egypt, its peoples and their traditions, offering evidence and insight at every turn, through the Age of Empires until its conquest by the armies of Rome, headed by Octavian, later the Emperor Augustus, in 30 BC. A memorial to Sir Alan Gardiner (1873-1963), “a modern scribe” and one of the foremost experts of his generation in Egyptian languages serves to highlight that these galleries are also the story of the place of the Ashmolean and Oxford University in the development of archaeology, Egyptology and the study of ancient civilisations.

During The Leisure Review’s visit a school group were showing huge enthusiasm for the mummification process but in noticeably hushed, almost reverential tones. Whether this was in response to the mummies or the new galleries was not certain. The only question that remained as we completed our tour of the new space was what had happened to the old space: where was the museum shop? A sign directed us to the lower ground floor where, among the Exploring the Past galleries, the new shop can be found, handily placed for the cloakrooms and the café.

Jonathan Ives is the editor of The Leisure Review.

The Leisure Review reported on the Ashmolean's redevelopment in February 2010.

The Leisure Review, February 2012

© Copyright of all material on this site is retained by The Leisure Review or the individual contributors where stated. Contact The Leisure Review for details.

Download a pdf version of this article for printing

The Min statues: phalluses, perhaps mercifully, missing

The Min statues: phalluses, perhaps mercifully, missing