Marcel Duchamp: his part in my downfall

London’s Barbican has announced that it will host a four-month celebration of the work of Marcel Duchamp in 2013, a programme of events and exhibitions that will confirm him as the greatest cultural figure of the modern era. Nick Reeves explains why.

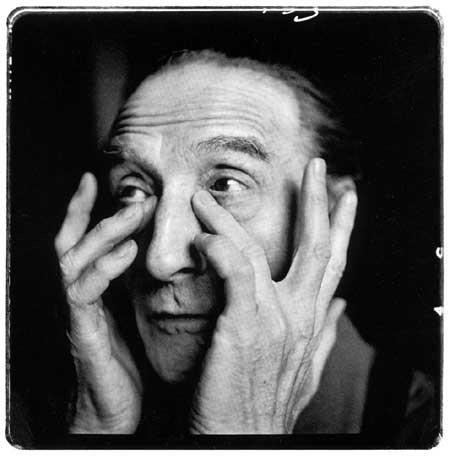

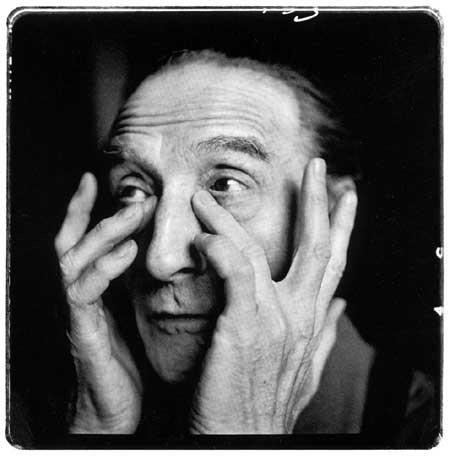

“The most singular man alive,” Andre Breton called him, “as well as the most elusive, the most deceptive.” The enigmatic Marcel Duchamp (1887- 1968) has been claimed as the most influential artist of the modern era, outstripping Picasso. And it’s true. Duchamp has done more to change our perception of what art can or cannot be than any other artist. Although he died in 1968, his work still resonates and asks a number of thought-provoking questions about art, about life, about everything. He was the prince of absurdity and mocker-in-chief.

In a post-modern era that has turned contemporary art into expensive commodity for wealthy elites and propelled artists on to rich lists, it will be refreshing to see and re-evaluate the work of a man who thumbed his nose at gallerists and the art establishment, and changed everything. A Marcel Duchamp season will open at the Barbican in London on 14 February next year and will run until June. Called Dancing around Duchamp, it will reaffirm Duchamp’s remarkable impact on all the arts and art theory. Essential viewing? You bet.

But why is Duchamp important? After all he had no sense of it, himself, or ever took anything seriously. Well, he made us reconsider what a work of art is – and who decides. And he brought home the notion that art can be a joke: the absurd for him was the ultimate seriousness. In fact he opened up untold aesthetic possibilities which have seen fruition in Dada, Surrealism, Nouveau-Realisme, Neo-Dada, Pop and Conceptualism. Those who think that Damien Hirst, Sarah Lucas, Tracey Emin and the rest of Nick Serota’s gang were pushing the boundaries should think again. Duchamp beat them to it with his Urinal, Snow Shovel, The Large Glass, Three Standard Stoppages and the other ground-breaking work he was doing between 1912 and 1928.

But if ever there was a watershed between the artistic past and whatever the present turns out to be, it was Duchamp’s Snow Shovel(given the mystifying title: In Advance of the Broken Arm), that quite unprepossessing object which in 1915 left the safety of a shelf in a hardware store in upper Broadway for the perilous pleasures of the world of art. What an odd fate for something so banal and commonplace! It was never to be quite the same again, nor, which is more mysterious, were we. For of what other object, man-made and mass-produced (pace the plane and the bomb), can it be said that, because of one man’s decision, the course of culture was altered forever?

The Snow Shovel, then, was the ultimate insult, far worse than the other readymades or Mona Lisa’s moustache. They were bad enough but they only offended our prudery and cult of the old masters and retinal art; and that was part of the fun. The Snow Shovel has never been fun or funny. Like some gauche and tiresome stranger in a pub, it seems never to have been meant to be liked. But now we cannot do without it. From now on we know that every work of art, whether prehistoric or conceptual, must be seen in its own terms, as part of a human, all-too-human situation – the triumph of consciousness over matter and, what is more important for us in this century, of will over taste. Maybe only one unfortunate shoveller may have broken his arm (the day after Duchamp acquired the shovel he read in a newspaper that a man had broken his arm shovelling snow) but Duchamp has twisted everyone else’s.

Giving up art for chess (at which he excelled and competed at international level) in 1928, Duchamp remained aloof from prevailing cultural trends watching silently and with amusement the impact of his work on others: the Urinal sent to an exhibition jury, the Snow Shovel bought in a hardware store, the stolen Bicycle Wheel placed on a stool; and his hirsute Mona Lisa. Yet the impact was huge and continues to this day. Art, film, photography, dance and music – nothing escaped Duchamp’s interest or influence. Yet his output was remarkably small and he gave very few interviews. And his masterpiece, The Large Glass, took eight years to make (1915 to 1923), starting with preparatory drawings begun in 1912. It is the prize item in the Philadelphia Museum of Art and, although very fragile, will be shown at the Barbican.

The last big show of Duchamp’s work in Britain was at the Tate Gallery in 1966. Organised by the Arts Council (when it had plenty of money), it was the largest retrospective of his work ever to be held in Europe and marked him as the most important artist-philosopher of this or any other time. The Barbican exhibition will fix Duchamp, once and for all, as a great (the greatest in my opinion) cultural figure ever. And although you may mock the cynicism of the merchandising that accompanies all blockbuster art shows these days, you will visit the Barbican’s shop. You will sneer at the Duchamp scarves, key rings and mugs. But, I guarantee, you will buy a replica of his iconic Urinal. Oh yes you will! And old Marcel, the master contrarian and prankster, will smile benignly, getting the joke.

I was in my teens when I saw the Tate retrospective and it convinced me then that after Duchamp there was nothing left for an artist to do or to say. Duchamp had, in effect, written the final chapter of art and put the full stop on art history. Any further attempt at art-making, I concluded, would be futile and merely repetition. Put simply, Marcel Duchamp was my downfall and ended any thoughts I had of serious art practice.

The son of a Normandy lawyer, Duchamp followed his two artist brothers to Paris in the late 1890s. He flirted with Cubism, Dadaism and Surrealism but, having resolutely refused to belong to any group, he determined to find his own voice. He wanted an art that appealed to the intellect as well as the eye and that made the viewer a participant in the creative process. Once his fame was assured he refused to work to order or to show and sell his work. He eschewed art as commodity and, apart from a few late works made for his own amusement, stopped making it. For the rest of his life he concentrated on playing chess and talking and joking with his closest friends and fellow Dada activists, Man Ray and Francis Picabia.

Duchamp was renowned for his warmth, easy-going charm and wit – so evident in his readymades and moustached Mona Lisa. And it was this that made him attractive to other contrarians like Man Ray, Picabia, Apollinaire, Erik Satie, Andre Breton, Robert Rauschenberg, John Cage and Richard Hamilton. But in his private life, as in his art, Duchamp remained elusive, living simply as a hermit in New York pursuing his interest in chess, mathematics, kinetics and jokes, and staying coolly uncommitted to making art for museums and millionaires.

However, having spent his life mocking art, corporate greed and those who made art their business, Duchamp, in the end, failed in his mission. He could not prevent the rise of a cultural industry in thrall to big business. And he could not stop the art establishment conferring power and praise on artists hell-bent on a career or from awarding PhDs to fine art students. After his death they took his anti-art, anti-everything message and made it respectable, and they gave his work the museum treatment. In staging the Duchamp festival next year the Barbican will establish Duchamp as a great cultural icon but undermine everything that he stood for. Oh irony of ironies.

Nick Reeves is the executive director of CIWEM and an exhibited artist of some repute. He is above all an enthusiast.

For details of the Barbican Duchamp exhibition see www.barbican.org.uk/artgallery

The Leisure Review, November 2012

© Copyright of all material on this site is retained by The Leisure Review or the individual contributors where stated. Contact The Leisure Review for details.

Download a pdf version of this article for printing