Allison: challenging the leisure sector to face and shape its future

Sport and/or health: the future of local authority sport and leisure services

With no sign of an end to the mantra of austerity, Martyn Allison considers the future of leisure in the public sector and offers some radical challenges for those looking to maintain a role for sport, leisure and culture in the UK.

Allison: challenging the leisure sector to face and shape its future

As we approach the next election minds are focusing on the future. The party conferences are outlining the options and next May we may (or may not) have a new government. The last few years have been a period of rapid and often transformational change, particularly for those working in or for the public sector. Nothing to me suggests the next five years will be any different.

The sport and leisure sector has itself undergone radical change and downsizing but continues to aspire to be a key player in the life of communities and individuals. This paper is my personal perspective on what this future could look like. It is designed to stimulate the sector to think how it might shape its own future rather than be a victim of other people’s change programmes. I believe the sport and leisure sector can come through this next period of change stronger and better positioned but only if it plans effectively for this change and invests in strong leadership.

Understanding the main drivers of change

Over the next five years I suggest there will be two primary drivers of change in the sector: the focus on physical activity and health reform; and austerity.

Physical activity and health reform

Those working in the sector have always believed that sport and leisure have wider community benefits, particularly health benefits, but have always found it difficult to convince others outside the sector. Over the last decade the emergence of scientific evidence on the value and importance of physical activity on people’s health has grown and it has been easier to make the case for the sport and leisure contribution. However, progress has been slow and patchy.

The Marmot review [note i], titled Fair Society Healthy Lives, published in 2008 outlines the arguments for and solutions to addressing health inequalities in the UK. It recognises that there were a number of social determinants of poor health and there is a need to address these wider influences on health inequality if we are to improve overall levels of health and close the gap between the richer and the poorer communities.

Among its conclusions and recommendations, many of which relate to prevention, including the importance of activity, was the revelation that “Focusing solely on the most disadvantaged will not reduce health inequalities sufficiently. To reduce the steepness of the social gradient in health, actions must be universal, but with a scale and intensity that is proportionate to the level of disadvantage. We call this proportionate universalism.” This concept, now quite widely accepted, underpins the role sport and leisure can play in the future. It provides the justification for sport and leisure providing access to physical activity for the whole community while focusing most resources on those in greatest need or most disadvantaged.

Success in terms of positioning sport and leisure as integral to health improvement and addressing health inequality has been at best patchy and general acceptance of the arguments is not the case across the country. Where the case has been accepted the impact has been spectacular, as in the case of the Birmingham Be Active scheme. When the case has been made well and relationships between health and sport and leisure are strong, partnerships have been built and resources have moved between the two sectors. These relationships have in some cases gone beyond health into adult social care, where the links between physical activity and older people living independently for longer are also becoming established. In a limited number of cases relationships have been extended into service personalisation, which enables vulnerable people with personal budgets to access leisure and recreational services. Finally, there are some early signs that relationships are also forming round the links between mental health and physical activity; as the focus on mental health grows so new opportunities will emerge.

However, just as the evidence has become better established, austerity has started to limit the ability of health services and adult social care to commission or procure sport and leisure services. Although the long-term costs of poor health and the impact of more people living longer is now recognised as a ‘ticking time bomb’, the political and professional challenges of switching declining resources from acute services to preventative services are difficult. Closing hospitals to fund an increased public health budget which in turn subsidises physical activity in local leisure centres or sports clubs is unlikely to win many votes. However, as the recently published NHS England Five Year Forward View [2] confirm, “the future health of millions of children, the sustainability of the NHS, and the economic prosperity of Britain all now depend on a radical upgrade in prevention and public health. Twelve years ago Derek Wanless’ health review warned that unless the country took prevention seriously we would be faced with a sharply rising burden of avoidable illness. That warning has not been heeded – and the NHS is on the hook for the consequences.”

Three key changes may influence such decisions in the future. First, the transfer of public health to local councils will bring decisions about priorities within the sphere of local councillors as opposed to health professionals. Second, the creation of health and wellbeing boards, often chaired by council leaders or cabinet members, will also allow local priorities to be influenced and service priorities to be shaped. Finally, the transfer of budgets to GPs and clinical commissioning groups could bring decision-making closer to local communities; and, as GPs are increasingly faced with rationing decisions, we may find that the preventative agenda becomes financially more appealing to them if it saves their budgets upstream.

Despite these potential positive changes, the challenges for sport and leisure will be huge as indicated in the recent changes in NICE (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence) guidelines on exercise referral schemes [3]. Over the last few years we have seen some GPs prescribing access to physical activity to patients, often picking up the costs of such referrals. The latest guidance from NICE seems to suggest that while physical activity has positive benefits on health, funding it does not represent good value for money unless it is associated with addressing a specific health condition or the risk of such a condition, for example obesity, stroke, diabetes or a chronic heart condition. In the future GPs and health commissioners could limit resourcing relationships with sport and leisure to specific clients with long-term health needs or risks rather than funding generic mass physical activity programmes.

So while the case for sport and physical activity contributing to health improvement and health inequality can be made, the ability to do so depends on the voice of the sector being heard around the strategic tables in councils and their strategic partnerships. However, there is evidence that this is not happening and the sector’s ability to influence strategic decision-making locally is becoming more difficult. In many cases there is now no senior leisure officer in many councils. In many more externalisation to trusts and contractors has almost completely separated the providers from the key political decision-makers and commissioners, while most district councils find themselves completely divorced from health and wellbeing boards operating at county levels.

Other evidence emerging from work to look at the relationship between sport and leisure providers and commissioners, currently being carried out by Sport England and cCLOA, is highlighting other challenges. This work has confirmed that the sector is still seen by commissioners as: lacking an understanding of commissioning and the commissioning process; selling sport, very traditional and facility-biased; more focused on making the active more active than focused on the inactive; more focused on increasing demand and income than meeting need; and still lacking in local data and evidence of impact and value for money.

Although health and wellbeing may be the primary outcome area for the sector to focus on, it is not the only one. Economic development, community safety, children and young people still offer important positioning ports for the sector but few of these are able to offer the same potential income streams, so perhaps it is really now time for the sector to “turn and face the money”. However, for this approach to be fully effective the sector will need to position itself at the heart of the transformational change programmes taking place across local public services and position itself as a strategic provider of better community outcomes, not just a provider of sport and leisure services and activities. In doing so it will need to reassess how it provides these outcomes, which in turn will lead to very different patterns of service delivery. In fact, it will need a fundamental change in approach and mind-set across the sector.

Austerity and the capacity and capability to reform sport and leisure services

Austerity will remain a primary driver of change as the new government continues to get control of the deficit. There are choices in how this will be done, including between tax and cuts and in the speed and focus of policy options. However, whatever the choices, public expenditure will not grow and sport and leisure will continue to be challenged on efficiency and effectiveness. Looking nationally, exchequer expenditure will not grow but as long as the national lottery remains Sport England will continue to be a significant funder of capital development and initiatives that seek to increase participation. A new government will stimulate some policy shifts around the edges and the usual competitive tensions between sport for sport's sake and increasing participation will emerge but I do not expect radical shifts in thinking and direction. Councils will remain the biggest providers of sport and leisure but the overall value of their funding will continue to fall. The focus will increasingly be on achieving subsidy-free provision wherever possible, mainly through facility rationalisation and improvement but with some facility closures. Where a subsidy remains it will increasingly be targeted on individuals and communities with specific social and economic need, and tightly linked to the achievement of specific outcomes. These outcomes will be principally but not solely in the arena of improving health, addressing health inequality or in some places addressing ill-health or potential ill-health. The source of these subsidies will come not only from traditional leisure budgets but also from public health funding and wider health budgets now controlled by clinical commissioning groups and GPs but only where priorities match and performance is both evidenced and good enough. Leisure providers of all complexions – facilities, sports development, clubs and voluntary groups, county sports partnerships (CSP) and national governing bodies (NGB) – will therefore need to develop very different business models if they are to survive austerity.

Without adequate capacity and capability the sector is likely to face only negative change, which will undermine its positioning and performance and could well lead to a steep cycle of decline. With adequate capacity and capability the sector can create positive change and therefore sustain its own development and survival.

Over the last five years capacity has undoubtedly diminished at all levels but it is at the senior level where the impact is being felt the most. The loss of senior voices round strategic tables reduces our influencing ability. In many parts of the sector a leadership vacuum has appeared or is developing. With limited capacity the current fragmented nature of the sector further exaggerates the problem. The available leadership is fully stretched and often over-focused on operational management, so limiting their ability to influence and be influenced. Personal observation suggests that previous evidence of a tripartite sector still remains. One third of councils where there is strong political and managerial leadership are not just surviving but growing and sustaining a future. A second third could easily do so with the right help and support. The final third, where leadership is poor, have failed or are failing. A similar analysis I suspect could be made across NGBs, clubs and CSPs.

Leadership development therefore remains a key priority but little is currently going on and most that is taking place is fragmented within individual organisations or sub-sectors, for example NGBs and CSPs, rather than coherently across the sector. At the same time leadership demands are expanding and changing. For example, simple models of partnership working are no longer adequate in the new world of transformational change and rapidly need to be replaced with models of collaborative leadership capable of working across agencies and organisations. Such approaches need very different patterns of behaviour and leadership styles, patterns that move the sector from a culture of competition towards one based on real collaboration.

Capability also remains a challenge. Austerity has driven out resources for training and development. Some organisations have chosen to stop investing in training and development altogether. Individuals claim they are either prevented from travelling to training events or simply do not have time to do so. Former improvement-based support, including self-assessment tools, peer review and shared learning opportunities, have all but disappeared yet there remains a huge desire to access and learn from best practice and much good practice still exists across the sector. Quest and the National Benchmarking Service (NBS), key tools to aid improvement, have survived the initial phase of austerity and Quest is now showing signs of limited growth. However, we still have only 621 facilities accredited in the Quest scheme and only a small number of facilities have used the NBS to benchmark their levels of efficiency and effectiveness. The appetite for such tools remains constrained by the costs compared to the perceived benefits, which continues to limit our ability to properly understand how our facilities are performing and then use limited resources better.

CIMSPA, the sector’s mechanism for demonstrating it is committed to being professional, has struggled since its formation. Membership remains static and only 31 members have yet been accredited as chartered members. This lack of engagement has seriously inhibited the ability to provide high-quality training opportunities. A new start last year has reinvigorated the organisation and a new professional development framework has been published; new training programmes are starting to be marketed through independent accredited providers. However, the next 12 months will dictate the future of the organisation and unless membership growth is seen soon a future will not be sustainable.

Observing the sector recently in various contexts, I am increasing coming to the view that we have a fundamental problem emerging in terms of skills and competencies, a problem that needs to be recognised and addressed.

Much of the sector, particularly facility management, NGBs and club management, are demand-led organisations. Their background and culture is driven by a desire to increase demand, usage and therefore income. Their primary management skills are mainly in customer service, marketing and business management underpinned by technical skills in building and plant management, product development and programming.

The increasing focus on delivering better community outcomes, and in particular health improvement, requires a much greater understanding of, and focus, on meeting needs. Sport development has traditionally provided the needs focus, having been primarily responsible for attempting to increase participation, particularly among hard-to-reach groups. Although some of the skills and competencies are common to facility management, the behaviours and organisational culture are often different. In the past there have always been tensions between sport development and facility management because of these different perspectives and cultures.

Faced with resource reductions, the trend in councils has often been to downsize sports development in order to retain and protect facilities but at the same time clients expect facility management to accept greater responsibility for meeting social priorities by reaching out to hard-to-reach groups where they are measured against outcomes rather than commercial outputs. The tensions between demand-led cultures seeking to increase and sustain income to survive and clients requiring better social outcomes is bringing new tensions whatever the management model: in-house, trust or private contractor. The more facility managers look to interface with health and social care simply to create new income streams, the more these cultural tensions will be exposed. As evidence for the scale of the challenge, let me cite how difficult it has been to get facilities to assess themselves against the outcomes benchmarks within Quest Plus. To date very few have chosen the Measuring Impacts and Outcomes and the Contribution to Health and Wellbeing, Increasing Participation and Community Engagement options, continuing to prefer the more operational modules such as Sales and Retention, Fitness and Health and Safety, where they know they can score more highly. However, from November Community Outcomes will become a required module rather than an option and it will be interesting to see if such a move drives down engagement with the scheme. It is also worth noting that when faced with choice managers readily choose the efficiency elements of NBS over the effectiveness elements. Efficiency is clearly more important to them.

If facilities, NGBs and clubs are to successfully merge demand-led performance with needs-led outcomes, new training and development requirements will need to be met. The issue is by whom and how this can be done when resources will continue to be scarce. How well the sector responds to this challenge will dictate whether capacity and capability results in positive as opposed to negative change.

An integrated model for sport and leisure provision

So how might the sector respond to these two key drivers of change, given its current state in terms of capacity and capability? How can we successfully weld together a demand-led approach that maximises efficiency and removes the need for subsidy with a needs-led approach that addresses social outcomes, health improvement and health inequality? How can we then position the sector at the heart of transformational change that will deliver better health and social outcomes?

First, the sector must be prepared to see itself primarily as a provider of better health and wellbeing rather than a provider of sport and leisure. This will be very difficult for those who are passionate about sport for sport’s sake and are culturally rooted in traditional sport and recreation services that focus on the development of sport participation as opposed to physical activity. It will bring policy challenges for Sport England, the Sport and Recreation Alliance, NGBs and many sport clubs but I believe it will be the only way of resolving the medium-term financial crisis in the sector. However, the term ‘wellbeing’ is perhaps broad enough to encompass a wide range of social outcomes associated with community safety, community cohesion and work with children and young people, rather than being exclusively focused on health.

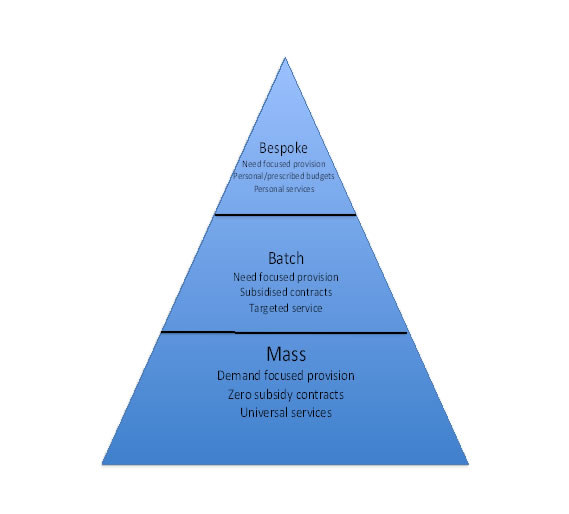

Second, the sector needs to understand and embrace the Marmot concept of proportionate universalism as the underlying principle on which the sector operates. This legitimises the need to distinguish between a physical activity service that is made available to everyone (universal) and needs-led services that are only provided to those disadvantaged socially, economically or in terms of their health (proportionate). Once this has been accepted it allows for a clearer distinction and transparency in how services are to be funded.

The universal service provided by facilities and sports clubs should aim to be subsidy-free. These traditional demand-led services should be encouraged to operate a universal service that is dependent on efficient business practices that will enable income to match, and if possible, exceed expenditure. Price can then become much more sensitive to, and be more determined by, the local market than the client specification, provided that its pricing policy promotes universal access and does not prevent it.

Is such a model feasible and realistic? NBS data now shows that more than the top quartile of facilities assessed are operating subsidy-free or close to it with accessible pricing. Similarly, recent Sport England-supported new-build facilities provided as part of a facility rationalisation programme also show major improvements in financial performance to a point where subsidy has been eliminated. Such an approach will enable councils to maintain a universal sport and leisure service for their communities without requiring a general subsidy. It will encourage operators, whether in-house, trust or private, to focus on efficient management practices that increase use and participation levels overall, in turn improving universal health outcomes across the board.

Once subsidy-free universal services have been established councils are then able to utilise all or some of the resources previously used for general subsidies to deliver targeted subsidised services to those communities and individuals in greatest need. This need could be geographical, by sex, age or ethnicity, by economic and social status or to address specific health needs or health inequality.

As an example, Birmingham’s Be Active [4] initiative used funding from the public health budget to provide subsidised free access to leisure facilities, parks and to some other providers. Although every individual in the city was able to have some free access time, the most deprived communities were offered the most time, a form of proportionate universalism. The scheme administered through membership cards currently has 400,000 members. The subsidy costs are justified not only in terms of increases in participation levels and general health benefits but also the long-term financial benefits; independent research has shown that every pound invested through the subsidy generates a £21 long-term saving in the city, mainly for the acute health sector. There is also mounting evidence in the Birmingham project and other similar projects that some individuals, once encouraged into physical activity through free use, change their behaviour and participate outside the subsidised scheme to become regular, fee-paying customers, thus creating further income growth for providers.

Finally, a further level of needs-led services, focused not so much on deprived communities but on individual health needs, can be developed. As discussed above, GPs and clinical commissioning groups will increasingly wish to focus on commissioned contracts for individuals or groups of individuals with specific types of ill-health that could be improved by access to physical activity. Obesity, strokes, diabetes and heart disease are primary candidates but even cancer, re-enablement and mental health may also be legitimate targets for intervention. Equally important could be the targeting of individuals with personal budgets who would choose to spend their budgets on access to sport and leisure service as well as personal care. Again, some of these individuals will move from targeted services to become fee-paying users. To benefit from these contracts sport and leisure providers will need to become much more accessible to commissioners by better understanding the local commissioning landscape and processes, building relationships with commissioners and being better equipped to evidence local impact and value for money.

The above diagram shows how these three different approaches to provision can be seen and managed as a fully integrated system at a local ‘place’ level or even within the context of a single facility or management contract. If a universal service offer can successfully be provided subsidy-free then needs-led services can be seen as generating a social and financial return, which can then be ploughed into service improvement and providing further needs-led services. Above all, the overall provision has now become financially sustainable in the long term.

Next steps

Many of you reading this paper will be suggesting that this vision is unrealistic and unachievable. I would disagree on the grounds that all the elements of this model are already in existence somewhere in the UK. The challenge is turning these approaches into a single, cohesive package and then replicating it across the country.

To do this six key steps are required:

The sector is at a key point in its future development. Now the gold dust of the Olympics has settled, the pressures of another five years of austerity could easily grind the sector down to next to nothing. There is no doubt that the relationship between physical activity and health is the new gold dust but to capitalise on that relationship we will need a significant step change in thinking and a commitment to transformational change across the sector.

Martyn Allison is a former national adviser for culture and sport at the IDeA/LGA, a chartered fellow of CIMSPA and chair of the CIMSPA membership committee. He is also chair of the QUEST/NBS board.

Notes and references:

[2] NHS England: Five Year Forward View

http://www.england.nhs.uk/ourwork/futurenhs/

[4] Be Active:

http://beactivebirmingham.co.uk

[6] Sport England support on health:

http://www.sportengland.org/our-work/local-work/health/

The Leisure Review, November 2014

© Copyright of all material on this site is retained by The Leisure Review or the individual contributors where stated. Contact The Leisure Review for details.

![]() Download a pdf version of this article for printing

Download a pdf version of this article for printing