Out of the shadows: evidence for effects of pedometer interventions is clear

After decades of urging practitioners in the sport, leisure and culture sector to adopt an evidence-based approach to their work, Carl Bennett is still finding sizeable pockets of resistance. How long, he wonders, before the well-documented lessons of behaviour change are adopted as part of an effective armoury of skills that can deliver the outcomes we need?

Out of the shadows: evidence for effects of pedometer interventions is clear

Over the past few years I have written many articles for the Leisure Review with a number aimed at stirring the evidence honey pot to encourage readers to take an evidence-based approach to their work. The fact that many people ignore evidence no longer surprises me but, as resources – people, facilities and actual cash – disappear as though Houdini himself had been reincarnated, it does concern me that when simple behaviour change evidence emerges it is met with disbelief by a sector-based audience that has probably never read a peer-reviewed article.

This is, I know, a big statement to make but, following many years of presenting at seminars and conferences to large numbers and testing awareness of evidence use and knowledge of its availability, it is one I am able to evidence.

Even with the new approaches the DCMS and Sport England have adopted in their recent strategies and funding announcements, there is limited support across the wider sector for evidence-based approaches, especially, it seems, to those approaches relating to behaviour change. This sometimes simple and often cynical refusal to adopt an evidence-based culture comes from within a sector that has been set a clear behaviour change challenge from the most strategic organisations steering the sport tanker; as such it represents a clear misalignment with my own evidence-based principles, which have sustained a long career in the sport, physical activity and public health sectors.

The recent appearance of another study citing the use of pedometers as an effective means to get people active has, it seems, been met with a quiet disbelief at best and a cynical glance at worst. The new peer reviewed paper, Effect of a Primary Care Walking Intervention with and without Nurse Support on Physical Activity Levels in 45- to 75-Year-Olds: The Pedometer And Consultation Evaluation (PACE-UP) Cluster Randomised Clinical Trial [ref 1], published in the Public Library Of Science , continues to build on the long-standing evidence that supports the use of pedometers as a successful behaviour change tool. The name of the paper would probably dissuade many people from reading it but many peer-reviewed papers have long-winded and often complex names; after all, academics have to earn their status.

Pedometers are often seen as an inexpensive product, easily activated, easy to use and understand, easy to pass on to a friend or family member once you have finished with it, all too easy to drop down the loo, and far too easy to leave in a drawer and be forgotten about if interest is lost.

The point often missed is this: they do help sedentary people become more active more often. This evidence has been universally accepted.

Let’s take a step back (pun intended).

Many of us will have received a pedometer from a colleague, family member or friend, a local or national health initiative, or as a gift from an event, conference or seminar. Can you recall the first time you received a pedometer?

How did you feel? What did you do? Did you start using it right away? Did you record/log your steps? Did you increase your steps over time? Did you set a goal? Did you compare your steps with someone else? Did you drop it down the loo?

Regardless of the accuracy of the device, I suspect many of you answered ‘yes’ to a number of the above, if not all of them.

Now try to remember if anyone spoke to you about how you were progressing. Did they ask if you had increased your activity? Did they ask for a log of your steps/activity? Were you asked how you were now feeling? Did you move on to something else? Was the use of the pedometer a catalyst for change?

Fewer of you will say ‘yes’ to these questions. This is probably because whoever gave you the pedometer didn’t follow up with you, although this is less likely to be the case, believe it or not, if you received your pedometer as a hand-me-down. Your friend, family member or work colleague would have asked how you were getting on. You probably didn’t need prompting: you most likely told them, on many occasions.

The more ‘official’ the route from which you received a pedometer, the more likely it is that you didn’t even get a call, unless you were part of a control group or a health initiative. Even then, you were probably ‘lost to contact’ and follow-up stopped. For the cynics this is where the sector fails; and it fails on a number of levels, including:

Here is where the evidence comes in.

Follow-up is crucial. As a whole, the sector really does fail to follow up. We fail to follow up with those people whose contact details we have. We now collect more information from people than ever before. We have email addresses, mobile numbers, landline numbers, home address and place of work. We have Facebook and Twitter handles, we use WhatsApp, we use FB Messenger and many other social media applications. Yet we still fail to engage. We fail to communicate. Many fail to utilise the often complex membership retention systems that have realised significant investment to introduce. We don’t even call…

The evidence often cited with the use of pedometers is more often than not linked to the use of follow-up contact. This is the evidence I take from the paper that this article is based on [ref 2]. The new evidence confirms previous evidence which has roots back to 2006. This is a good thing. There are lots of examples on which to build an intervention. Lots of examples of what works. Lots of examples of how you need to shape products and services. Lots of examples that say the most effective way to help someone become and remain active is to take an interest and communicate.

For anyone who is taking their first steps (another pun right there) towards a more active lifestyle the basic principle is to take an interest by calling them or asking them to attend a regular follow-up. However, this is often lost on a sector that relies on cash cows, products and services more akin to a factory floor rather than an activity growth cycle.

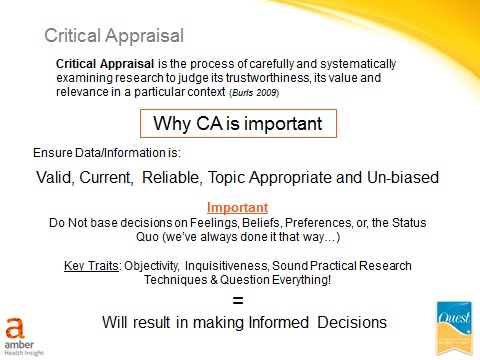

Of course, sometimes it is appropriate to be cynical about things you read. Many of the tabloids and Google searches present conflicting views of the health gains reported by many organisations and products; sometimes misrepresentation of sound evidence can inform our thinking and decision-making. In fact, good critical appraisal is a core competency many fail to hone, so when a critical viewpoint is shared it is often based on perception, beliefs, values, culture or past behaviour rather than independent critical appraisal skills that have been developed in line with emerging evidence and the formats in which evidence is presented.

I’m hoping the slide shown here, which is taken from the health master class slide set I delivered for Quest and one that has been used in numerous seminars and conferences I have delivered at over the past 20 months, will help you recap on the need to develop critical appraisal competencies and help you make informed decisions about emerging research and evidence.

Here is my message, which I hope produces an aligned behaviour change sector that has taken the challenge set by the DCMS and Sport England seriously.

Could it ever be as simple as this: in the future we will have a sector that has accepted the challenge from the highest strategic organisations in the land, and has generated a proven track record of utilising evidence to inform, shape and challenge the products, services and programmes on offer? When this happens it will be easier to demonstrate how simple behaviour-change interventions have been interwoven throughout the programming offers that are now seen as the real generators of healthy communities, rather than generators of short-term cash to offset deficit challenges. And is it as simple as a sector workforce that has a number of core behaviour change theories and skills, including critical appraisal, within an armoury that has helped them become more effective, efficient, engaged and recognised for the impact and outcomes they now produce?

Carl Bennett is a health insight and health improvement specialist. He is also a visiting fellow of Staffordshire University.

References:

[Ref 1] Effect of a Primary Care Walking Intervention with and without Nurse Support on Physical Activity Levels in 45- to 75-Year-Olds: The Pedometer And Consultation Evaluation (PACE-UP) Cluster Randomised Clinical Trial

Published: 3 January 2017

[Ref 2 ] Four commonly used methods to increase physical activity

Public health guideline [PH2]

Published date: March 2006 Last updated: March 2015

The Leisure Review, March 2017

© Copyright of all material on this site is retained by The Leisure Review or the individual contributors where stated. Contact The Leisure Review for details.

![]() Download a pdf version of this article for printing

Download a pdf version of this article for printing