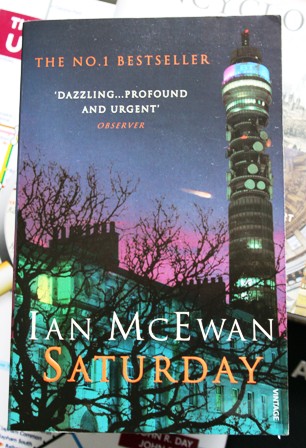

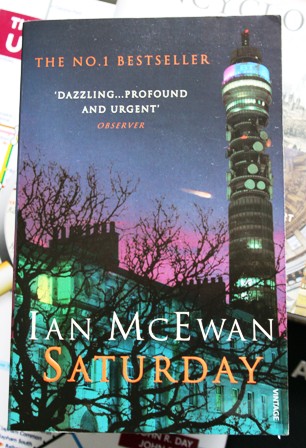

No 3: Saturday by Ian McEwan

What’s it about?

One day in the life of Henry Perowne, neurosurgeon. It is, as the title of the novel implies, a Saturday but not any Saturday. It is Saturday 15 February 2003, the Saturday of a public protest against the invasion of Iraq, a protest that is to become the biggest anti-war march the capital has ever seen. It is the Saturday scheduled for a family reunion, with all the usual enjoyments and antagonisms that families entail. And it is the Saturday when the wealthy, successful and secure Henry Perowne runs into a thug called Baxter. The story takes us from early in the morning when Perowne wakes, unusually disturbed from sleep on his day off, through to the late evening when his day off sees him back at work. In between are the events that change lives.

What’s it got to do with leisure?

Inside the head of his protagonist the author explores the questions of art and science, the competing merits of art and sport, the nature and technique of blues guitar, the challenges and rewards of literature, not to mention the agonies of magical realism. While all this swirls around Perowne’s head, we are really here for the game of squash, the 17-page descriptive set piece which has gained the novel a certain notoriety. Few books dedicated to the game of squash would presume to take such a detailed approach to a single match and here McEwan puts himself among the very few novelists who would dare to attempt to hold the reader’s attention for so long with something so ostensibly mundane.

Why should I read it?

McEwan is among the acknowledged greats of the modern British novel and this is a bravura performance. In Saturday McEwan is setting himself a number of challenges. There is the squash game, of course, but there are also the complexities and ethics of neurosurgery, the story’s 24-hour format, the precision of the novel’s construction in plot and tone, the meticulous sense of place, and even the exploration of marital fidelity, not a subject often chosen to drive stories to the brink of excitement and beyond. The extent to which he brings off these challenges is for the reader to decide but this is clearly the work of a highly skilled author with great confidence in his abilities as a story teller. The use of the historic present lends pace and the sense of unease within Perowne’s comfortable and familiar world is finely wrought, while the unpredictability and discord of a massive political demonstration is established as a counterpoint to the certainty and steadiness of Perowne’s professional and personal existence. However, it is the precision and the meticulous detail that sets the reader a challenge. Anyone curious about the finer details of neurosurgery will find plenty to interest them but there is a nagging feeling that no research has been wasted. Is the squash game an example of an author in full command of his powers or a literary exercise? Does the story of Henry Perowne present, as one review suggested, “an Everyman for our times” or is a wealthy neurosurgeon with a townhouse in Fitzroy Square, who wears “an old cashmere jumper with moth holes across the chest… [and] a track-suit bottom, fastened with chandler’s cord at the waist” to play squash, whose wife is a celebrated lawyer, whose son is an up-and-coming blues guitarist and daughter a newly published poet, just too far removed from the realities of the world on the streets just beyond those where he spends his time to warrant our sympathy or our attention? Ian McEwan’s Saturday certainly keeps the pages turning but whether it gets beyond the conventions of a thriller to reach the shelf marked ‘literature’ is a moot point.

Download a pdf version of this article for printing

the leisure manager’s library

An occasional series offering a guide to leisure-related literature