Kay Adkins, hot tub correspondent

Edition number 7; dateline 30 May 2008

Why should sports people make the best sports coaches?

After attending the UK Coaching Summit and, of course, reading TLR’s report on the gathering of the coaching glitterati, my ponderings turned to coaching. I suppose my thoughts don’t often stray too far away as, although I dabble in many areas of work, coaching and the development of coaches is my first love and I still spend many hours working with SportsCoach UK delivering coach educator workshops.

Anyway, back to my ponderings. A few months ago I had the opportunity to go on a training course to learn how to be a business coach and I was intrigued to find out the differences between business coaching and sports coaching. I was actually quite nervous as I was going to be among all these business types and what did I know? I’m just a humble sporty person and it is well known that ‘jocks’ aren’t very bright!

When I arrived my fears were heightened as all the other course participants were in fancy business suits while the rebel in me had forced me into a more sporty outfit. I was going to be out of my depth. The course started and worse was to come as most of them were already business coaches or ran multi-million pound companies. But my interest was piqued when I said that I came from the world of sports coaching and all of their eyes lit up – surely my humble profession wasn’t up to their giddy heights? Then, not long into the course, the tutor started talking about Sir John Whitmore (international coaching guru and former racing driver) and a squeak emanated from me: “I’ve worked with him. I used to deliver a workshop with him and David Hemery.” Gasps came from around the room and the tutor went a pale colour, which surprised me as I was a sports coach and more used to people shouting at me! I guess where this story is taking me is that I was unaware that the experiences I had in the sports world would have any standing anywhere except in our own sphere. I had underestimated the knowledge I could bring to the ‘party’.

Which brings me to our response to new people coming into the coaching profession: do we give them respect for the experiences, skills and knowledge they bring with them into the sports world? Perhaps not as much as we should. Even now after over twenty years in this game I still hear people debating whether individuals who have played sport, often to a high level, would be better coaches or more ‘appropriate’ coaches than those who aren’t steeped in the history of that game. Is this true?

Is it easier to train coaches that have a good playing knowledge of the game? Well, I guess if we want them to be technical experts who tell the participants how to do something then yes it is easier to take people who know the particular sport inside out and get them to regurgitate the coaching manual. Perhaps I am being a little hard on those who do come with a good technical knowledge but sometimes I find this group are the most difficult to turn into what I think is a good coach because they bring with them the baggage of how they were coached and/or how they communicated with team mates – different communication skills to that of the modern coach. Given that qualifications being offered within the UK Coaching Framework (UKCF) are all based on the premise that we should ‘ask’ – or even ‘delegate’ – rather than ‘tell’, the I-know-best school of coaching is a dying breed.

When I ask the question of people training to be coach educators what makes a good coach, I get the following answers:

• good communication skills

• well planned

• inclusive

• safe

• a good role model

• they want to carry on learning

• good questioning skills

• knowledge – sports science and tactical/ technical

So could a nurse, a sales professional, someone who works in tourist information bring all the above, except the technical/ tactical knowledge, and do them very well? My experience is that they can and do. Yes, they do need the technical knowledge and it is much better if they have played a bit (doesn’t matter what level) but it is actually easier for the coach educator to support them into being a good coach than it is changing the habits of the seasoned performer who has perhaps been coached badly for many years and brings that experience with them.

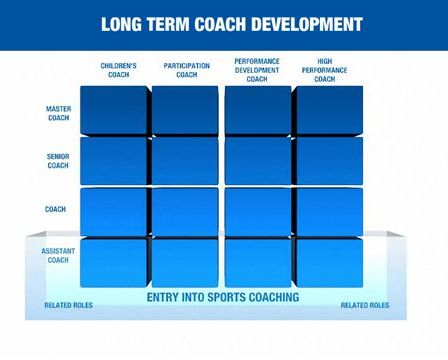

Going again to the UKCF, which after all has been written by a raft of very clever and experienced people, I dug out a diagram (shown on the right). The 4x4 model of coach development is revolutionary because it challenges the belief that the highest qualified coaches should work with the highest level performers. Why shouldn’t children be coached by the very best coaches – the master coaches from the diagram? Isn’t that where our best efforts as a nation should go – into our young people? Of course what my TLR colleagues would probably call the corollary of this is that beginner coaches don’t need to work with beginner players. After all, Martin Johnson hasn’t been on a single coaching course in his life but he’s in charge of the coaching of this decade’s best rugby squad the world.* Don’t be fooled into thinking that coaching mastery comes from knowing more than the players. Ask yourself this: who knows most about playing centre for the under-12s netball team, an eleven-year-old who plays there every week or her forty-year-old, ex-county-playing, twenty-years-a-teacher coach?

The reality is that good coaches come from a variety of backgrounds and all will require support and nurturing in different areas. The sports person may need much more work on people skills whereas the non-sports person may need additional help with learning the technical/tactical elements of the sport but we shouldn’t reject anyone who may be a good coach. Come on, let’s be a little more open-minded in how we recruit people (taking into consideration all the necessary safety checks, of course) and let’s openly encourage those with non-sports skills. After all, the best coaches are those that ask the right questions of their performers and do you need to have played for twenty years to be able to ask good questions?

Kay Adkins is an executive board member of a county sport partnership, chair of a CSN and a member of the interim board of the National Skills Academy for Sport and Active Leisure. Kay is also managing director of KAM Ltd, which offers a range of support services in the sport and leisure industry working in volunteer/workforce development and facility development

* This ‘statistic’ was created by taking performances in the 2003 and 2008 Rugby World Cups – and nothing else – into account.

View from the hot tub

The last word in contemplative comment on the leisure industry

Kay Adkins, hot tub correspondent